MBRRACE-UK perinatal confidential enquiry

The care of recent migrant women with language barriers who have experienced a stillbirth or neonatal death

State of the nation report

Sara Kenyon, Ian Gallimore, Tina Evans, Georgie Page, Allison Felker, Alan Fenton (editors), on behalf of the MBRRACE-UK Collaboration. For additional contributors, see the acknowledgements.

Contents

Introduction

1.1. Report overview

This report presents the findings of the sixth perinatal confidential enquiry carried out as part of the MBRRACE-UK programme of work, and investigates the quality of care provision for women who are recent migrants with language barriers and whose pregnancy ends in stillbirth or neonatal death. This topic was selected by the Maternal, Newborn and Infant Clinical Outcome Review Programme (MNI-CORP) Independent Advisory Group following a call for topic proposals. Unlike previous enquiries, this was as a joint enquiry between the MBRRACE-UK perinatal and maternal programmes. The enquiry assessed care provision along the whole care pathway to identify areas of care requiring improvement.

A summary version of the report is also available to download as a PDF

1.2. Terminology

In this report we use the terms ‘women’ and ‘mothers’. However, we acknowledge that not all people who access perinatal services identify as women and mothers, and that our recommendations apply to all people who are pregnant or have given birth. Likewise, use of the word ‘parents’ includes anyone who has the main responsibility of caring for a baby.

2. Background and methods

2.1. Context for the enquiry

Like other high-income countries, the UK has seen a steady increase in migration. By 2022, 14% of the UK’s population was born abroad, with 4% being asylum seekers or refugees. This trend is also evident in maternity services. In 2022, nearly 1 in 3 live births in England and Wales were to women born outside the UK, the highest proportion on record.

Research shows that migrant women, especially asylum seekers and refugees, experience maternity services differently from UK-born women. Many delay booking their pregnancies due to unfamiliarity with the system and face additional barriers, especially if they have limited English proficiency.

As the rate of immigration continues to rise, UK maternity services must adapt to address the unique needs of migrant women, particularly those who may face additional obstacles to access due to language barriers. This enquiry aims to identify lessons to improve the care and outcomes for these women and their babies.

2.2. The confidential enquiry process

As detailed in previous MBRRACE-UK reports, a confidential enquiry is a process of systematic, multidisciplinary, anonymous review where a consensus opinion is reached about the quality of care provision for all cases undergoing review. Our previous confidential enquiries have demonstrated the ability of this method to make inferences about quality of care provision. However, it is important to state the potential limitations of this method. A confidential enquiry cannot identify other important differences in care that may have occurred but were not documented, or not sufficiently detailed in the clinical notes available for review. These could include biased attitudes of staff or any behaviours that may influence non-verbal communication, elements that can only be identified by collection of data directly from mothers and families about their experiences. A confidential enquiry also does not have access to information about specific organisational structure, practice and culture.

The basic premise of any confidential enquiry is “if it is not written in the notes, it did not happen”, as is the case for legal cases. Clearly this then relies on accuracy and completeness of note taking throughout the whole care pathway in both handwritten and electronic notes as well as reports and letters. This method does not provide an opportunity for individual parent feedback due to the confidential nature of these enquiries. In this enquiry where we are trying to determine not only whether standards and guidance were adhered to but also issues around accessibility, engagement and individual interactions with women during their care, it must be recognised that this can be very difficult to determine from clinical notes, letters and reports alone. This report is therefore limited to those issues where adequate information has been provided in order to allow more nuanced findings to emerge.

Each set of notes was first reviewed by individual clinical assessors: a midwife, an obstetrician, a neonatologist (all neonatal deaths plus any stillbirths where the family received input from the neonatal team), a perinatal pathologist, plus additional clinical specialties where required. The compiled reviews were then discussed by a larger, multidisciplinary group in order to reach a consensus view on the quality of care provision. Additional supporting data was extracted from the notes by the MBRRACE-UK Clinical Advisor using enquiry-specific checklists, in order to provide a description of the risk factors present and a detailed record of interpreter provision for each woman. This additional information provided contextual data and facilitated discussions around emerging themes.

As in previous enquiries the focus was on both good care provision and care which could be improved for women and their babies. The standard MNI-CORP criteria, adopted by all enquiries in the programme, were used to summarise the holistic assessment of the overall quality of care for each mother in terms of her psychological and physical well-being and future fertility, and baby in terms of any factors that may have affected the outcome. In contrast with previous perinatal confidential enquiries, and in common with the approach used by the maternal enquiries, assessors agreed an overall grading of care for each mother-baby pair (Box 1).

Box 1: Overall grading of care

- Good care, no improvements identified;

- Improvements in care identified which would have made no difference to outcome; [note 1]

- Improvements in care identified which may have made a difference to outcome. [note 1]

Note 1: Improvements in care should be interpreted to include adherence to guidelines and standards, where these exist and have not been followed, as well as other improvements which would normally be considered part of good care where no formal guidelines exist.

2.3. Eligible pregnancies

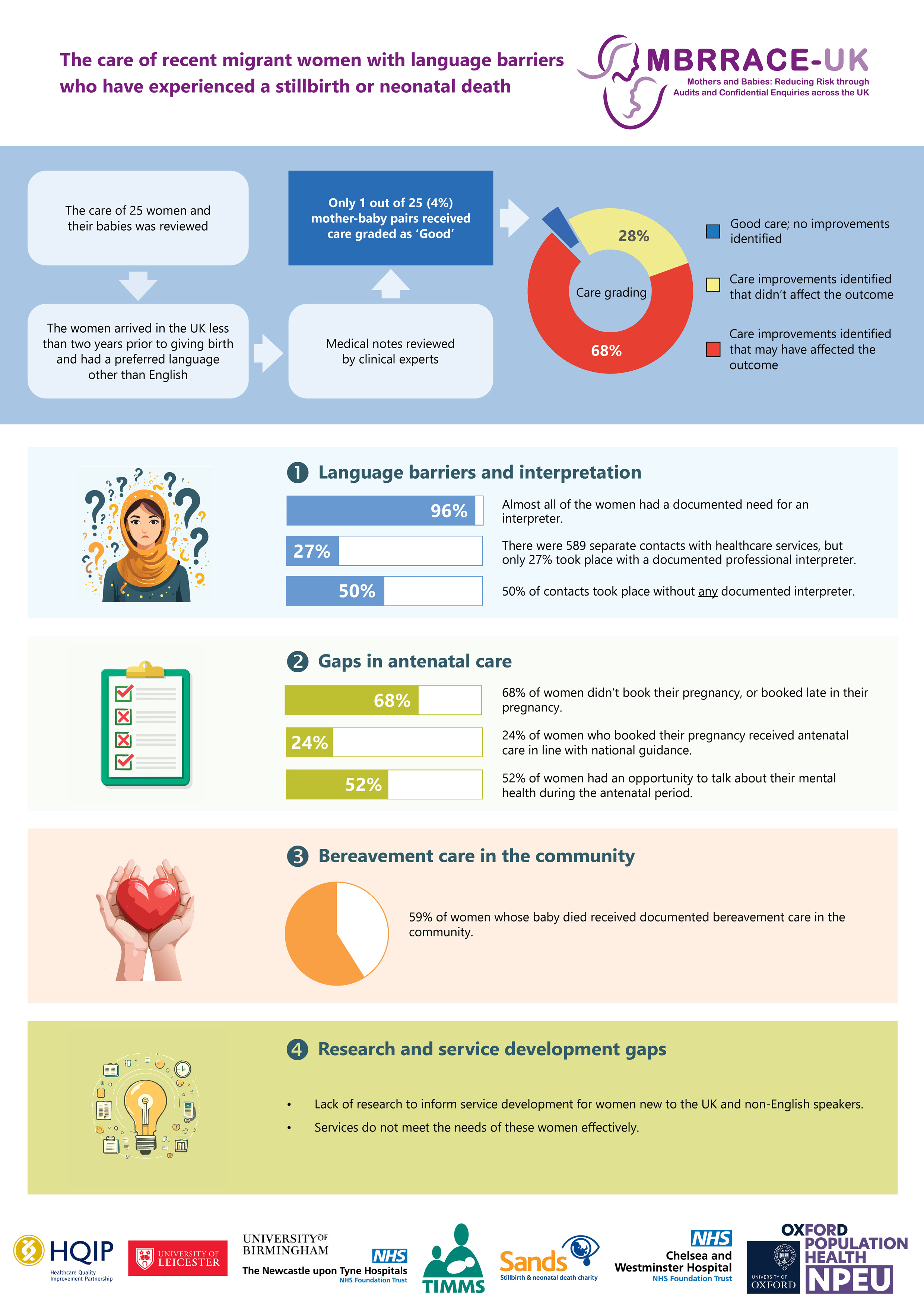

A stratified random sample of women who were born abroad, arrived in the UK less than two years prior to giving birth and were identified as having a preferred language other than English was identified from the MBRRACE-UK database of perinatal deaths or through routine national birth records for 2022. Of the 39 women identified from the two databases, 24 women experienced a perinatal death from 24 completed weeks’ gestational age and were therefore selected for review by the perinatal confidential enquiry. In addition, one woman did not experience a perinatal death, but received care from the neonatal team due to the presence of a congenital anomaly in the baby. In total, the care of 25 women and their babies was reviewed.

The majority of women were migrants from Asia (17 out of 25). Five women were migrants from Europe, and two were from Africa. For one woman (of Indian ethnicity), where she arrived from was not recorded in the notes. 15 women (60%) were not in their first pregnancy and eight women (32%) were known to be pregnant when they arrived in the UK. For most of the women who were not pregnant on arrival in the UK, it was unclear how long they had been in the country prior to becoming pregnant. Three women were known refugees, asylum seekers or arrived under one of the bespoke humanitarian routes to the UK. Citizenship status was not known or not documented for nine of the women whose care was reviewed.

3. Vulnerabilities in migrant women

3.1. Key findings

- Citizenship not routinely or accurately recorded for all women.

- Provision of interpretation services needed to be improved, with 73% of contacts taking place without documented professional interpreter provision from either an in-person interpreter or LanguageLine. 50% of all contacts took place with no documented interpreter provision.

- There was variation in the recording of social risk factors.

3.2. Citizenship

Citizenship was recorded for 16 of the 25 women: EU citizen (5), Non-EU citizen (7), Indefinite leave to remain (1), Refugee, asylum seeker or arrived via bespoke humanitarian route (3). For the remaining nine women citizenship was not recorded in the notes. Information about a woman’s citizenship is important, as it may impact on the ability to undertake an assessment of needs and personalise care planning. NICE guidance recommends that healthcare professionals receive training on the specific health, social, religious, and psychological needs of women who are recent migrants, asylum seekers or refugees, as well as current government policies on their access and entitlement to care. It is essential that clinicians are clear on the differences between refugees and asylum seekers and the different challenges faced by each group. In several instances it was noted that the proforma medical notes did not recognise this distinction, with clinicians only being able to record “Refugee/asylum seeker”. Two of the women recorded as refugees or asylum seekers came to the UK from Afghanistan and had settled status under the Afghan Relocations and Assistance Policy and Afghan citizens resettlement scheme, but refugee and asylum seeker were used interchangeably in the notes.

3.3. Ethnicity

Ethnicity was recorded for all of the women: Asian Bangladeshi (2 women), Asian Indian (2), Asian Pakistani (7), Other Asian (8), Black African (2), White (4). One Somalian woman’s ethnicity was incorrectly recorded in the notes as Asian rather than Black African. This same error was also noted for another Somalian woman in the previous perinatal confidential enquiry, suggesting that ethnicity was assumed rather than self-declared by the woman.

3.4. First language

None of the women’s first language was English and 13 languages were recorded, highlighting the challenges for services: Urdu (7 women), Romanian (4), Farsi (2), Bengali (2), Kurdish (2), Amharic (1), Arabic (1), Punjabi (1), Pashto (1), Somali (1), Tamil (1), Turkish (1), and Uzbek (1). The first language of one woman, who arrived in the UK from Afghanistan, was recorded variously as Uzbek, Dari and Farsi (the latter being the most common). All the women, with one exception (for whom it was not recorded in the notes), were noted to require an interpreter.

3.5. Provision of interpretation services

National guidance recommends that healthcare professionals should help support women to access maternity services using various methods of communicating information about antenatal care, and ensure that reliable interpretation services are available when needed. As noted in the previous perinatal confidential enquiry, where language is a barrier to discussing health matters, NHS England, NHS Scotland and Northern Ireland Health & Social Care guidance stipulate that a professional interpreter should always be offered, rather than using family or friends to interpret. There is currently no equivalent guidance for Wales. Detailed guidance is also given in the Migrant Health Guide. Within the maternity setting, NICE guidance also provides recommendations regarding the provision of interpretation services to facilitate information provision and communication between healthcare professionals and women. The Royal College of Midwives (RCM) has also produced guidance on caring for vulnerable migrant women.

The Migrant Health Guide states that tools such as Google Translate should not be used in health care settings as they are not quality assured. Rather, professional interpreter services, either remote or in person, should be used for every interaction. In total for the 25 women there were 589 separate contacts with healthcare services. The number of contacts per woman ranged from eight to 53. No interpreting was documented as being provided at 296 (50%) of those contacts. Recommended interpreting services (either a trained in-person interpreter or LanguageLine) were documented as provided for 27% of contacts, with a trained in-person interpreter recorded as being provided for 38 (6%) contacts and LanguageLine provided for a further 126 (21%).

| Type of interpretation | Number of contacts | % |

|---|---|---|

| Trained interpreter | 38 | 6 |

| LanguageLine | 126 | 21 |

| App or other tool | 17 | 3 |

| Family member or friend | 56 | 10 |

| Healthcare professional | 38 | 6 |

| No interpreter provision documented | 296 | 50 |

| Interpreter offered and declined | 18 | 3 |

Vignette 1: A recently arrived Iraqi woman received minimal professional interpreting services during her pregnancy, leading to significant language barriers despite being identified as needing interpretation at the outset.

A woman who recently entered the country from Iraq was identified as needing interpreting services when she attempted to book a telephone appointment for her pregnancy at 10 weeks. It was noted that these services would be necessary unless her husband was present, as she was new to the country and could not speak or understand English. At her subsequent face-to-face booking appointment, LanguageLine services were not available. She was asked if she could proceed by reading questions from a laptop screen.

Throughout her pregnancy, birth, postnatal, and bereavement period, 53 contacts with maternity services were documented. Professional interpreting services were used in only 2 of these contacts, and in one additional contact, an app or another tool was utilized. On three occasions, friends or family members were used as interpreters, and in four instances, the offer of interpreting services was declined.

During her pregnancy, it was noted that "the mother can speak a good level of English if you take your time" and that "no language barrier was found." Overall, 94% of this woman's pregnancy journey was not supported by the use of professional interpreting services.While there were some women who were provided with interpreting services for the majority of their contacts, no one had professional provision at every contact. Additionally, the assessors noted that women who had mainly good interpreter provision had complex pregnancies and were under the care of the obstetric team. This highlights the need for the care of these women to be coordinated by a dedicated team.

Interpreting was documented as being provided by a family member or friend for 56 contacts. In some situations, the assessors felt this was inappropriate.

Vignette 2: An Uzbek family struggled to discuss their baby's prognosis due to the unavailability of a professional interpreter, resulting in miscommunication and the abandonment of important discussions about memory-making, post-mortem examination, and Coroner involvement.

An Uzbek family was on the neonatal unit to discuss their baby’s prognosis, and despite repeated attempts over a twelve-hour period, a professional Uzbek interpreter was unavailable. The parents did not speak Russian, and an attempt to communicate with the mother’s English-speaking friend via speakerphone was made. However, the friend had to be repeatedly reminded to interpret only what the staff were saying, as she kept asking her own questions. The staff became concerned that the friend was not accurately interpreting the conversation, leading them to abandon the discussion due to concerns about the reliability of the interpretation.

Later that day, after further unsuccessful attempts to secure an Uzbek speaker through LanguageLine, the parents resorted to using Google Translate on speakerphone in the middle of the busy neonatal unit. As a result, the family was immediately relocated to the consultants' office, where a second friend was contacted by phone to serve as an interpreter during a discussion about transitioning to comfort care for their baby.

Because of the ongoing interpretation challenges, the team and family were unable to have detailed conversations about the cold cot and post-mortem examination. It appeared that the parents had subsequently changed their minds about memory-making, and there were concerns that they did not fully understand the need for possible Coroner involvement and the relevance of a post-mortem examination due to the interpretation problems.

In time-critical situations, use of an in-person interpreter may not be possible, and conversations via LanguageLine may be difficult. The most challenging stage of pregnancy care for providing interpretation services was during intrapartum care, where only 22 out of 72 (31%) contacts used either LanguageLine (16) or a trained interpreter (6). The lack of professional interpreter services was especially concerning during critical discussions or when sensitive information was involved, such as obtaining consent for procedures such as a caesarean section or explaining the importance of fetal movements during the antenatal period.

Vignette 3: A lack of translation services may have contributed to an Eritrean refugee's delayed reporting of reduced fetal movements, resulting in an emergency caesarean section and the subsequent death of her baby.

An Eritrean refugee booked her pregnancy and was referred to asylum support agencies for assistance. During her pregnancy, she reported three episodes of reduced or absent fetal movements. On two of these occasions, the episodes lasted three days before she accessed maternity services. Although the importance of reporting reduced or changed fetal movements had been discussed during antenatal visits, translation services were not provided during any of these contacts. It was unclear whether the mother fully understood the importance of reporting these episodes sooner. During her last presentation, where fetal movements had been absent for three days, a pathological CTG was identified, leading to an emergency caesarean section. Her baby died shortly after being admitted to the neonatal unit.

In addition to providing information in an appropriate format and language, an assessment should be made of the woman’s understanding. Ensuring understanding through closed-loop communication was considered crucial by the assessors. Tools such as the NHS Health Literacy Toolkit provide those working in healthcare with a number of tools to help support service users to understand and make decisions about their care.

When exploring the provision of interpreting services for routine and emergency care (attendance at the emergency department or triage), professional interpreting was documented as being provided for 35 of 94 (37%) of emergency contacts, using either trained interpreters or LanguageLine. Of 495 routine contacts, either trained interpreters or LanguageLine were used for 129 (26%). 36% of emergency contacts and 53% of routine contacts took place without any documented interpreting provision (50% combined).

In common with previous research, the assessors noted that interpreter use was not always well documented. Consistent documentation of each woman’s language needs and interpreter use (including where an interpreter is not available) is required, along with a mechanism for recording the number of women requiring interpreter services and the frequency of interpreter provision. This would help healthcare providers to provide targeted support to the women and families they care for.

With such low levels of professional interpreter provision, there are clear barriers to their use. Research should be prioritised to explore the barriers and facilitators to using interpreter services for women, their families, and healthcare professionals. Additionally, interventions to address these issues should be co-designed.

3.6. Social risk factors

We adopted the approach used by other researchers exploring the role of social risk factors and engagement with maternity services.

Information regarding social risk factors was identified by healthcare professionals' documentation in the case notes such as tick box checklists, appointment summaries or letters. This information usually originated from women, often at the initial booking into maternity care as part of a routine assessment, but may also have been added to or amended at later points. Information regarding ethnicity, nationality and citizenship was extracted from the notes, where recorded. Complex social risk factors were defined using the Revolving Doors Agency and Birth Companions criteria (Box 2). These were deemed appropriately addressed where they were identified and discussed or the woman was referred to support services by maternity care providers.

Box 2: Complex social risk factors

- Domestic violence or abuse

- Substance misuse

- Mental health issues

- Criminal justice involvement

- Homelessness

- Young age (under 20 years)

- Physical disability

- Learning difficulty

- Significant financial need

- Recent migrant (less than 1 year in UK)

- Unable to speak or understand English

- Social services involvement

Source: Revolving Doors Agency and Birth Companions, "Making Better Births a reality for women with multiple disadvantages".

As with the previous confidential enquiry, there was inconsistent recording of complex social risk factors within the notes of these women. The assessors felt strongly that, as a consequence, for several women safeguarding concerns were not escalated as they should have been. While social risk factors were identified in 10 women, the lack of use of professional interpreter services means this information may have been under-recorded. The main social risk factors identified were significant financial need (eight women) and insecure housing (eight women). Mental health issues were recorded for four women (two identified through routinely recorded data, two through an incidental finding). Social services involvement was recorded for two women.

Only 2 out of the 25 women received any form of mental health screening in the postnatal period and in only 13 of the women was there an opportunity for screening in the antenatal period. NICE recommends that women should be asked about their mental health at every appointment by a healthcare professional in order to raise any concerns they have and to ensure support is offered. They should have at least one opportunity to discuss sensitive issues without family members present on a one-to-one basis. Mental health assessments may not be as easily undertaken in situations where family members or partners are present. Additionally, research has highlighted the current lack of specific culturally safe services available to support migrant women in seeking and accessing perinatal mental health care. Future considerations should focus on the usability of existing screening tools that overlook cultural differences and how mental health is experienced, understood, and discussed.

Vignette 4: Despite early access to maternity services and stable mental health at booking, an Afghan woman’s deteriorating condition, including hallucinations and fear, was not communicated to maternity services by her GP.

A multiparous woman from Afghanistan accessed maternity services early in the first trimester. During the booking appointment, the community midwife noted that she had a long history of headaches and sleep difficulties that had never been resolved. Her mental health at this consultation was stable. At all of her antenatal appointments she was accompanied by her husband who acted as an interpreter. At the beginning of the third trimester, she was reviewed by her GP and a deterioration in her mental health was noted. She was experiencing hallucinations, hearing voices and was scared. Her husband stated that she was not ready for further psychosocial support, and information about her deteriorating mental health was not relayed to maternity services.

Screening is likely to be more effective and accurate when family members are not used as interpreters and it is vital that appropriate interpreting services are available to facilitate this process. However, this needs to be culturally acceptable to the women and their families in their specific circumstances.

The need for multiagency working was highlighted by the assessors, and while it was documented as occurring for some women, it was not consistent.

Vignette 5: A Bangladeshi woman received compassionate care during her pregnancy but was not adequately assessed for safeguarding concerns related to her social situation, lack of support, and other vulnerabilities.

A recently arrived Bangladeshi woman presented to a maternity unit in a different part of the country from her usual place of residence at just over 22 weeks of pregnancy. She reported a prolonged spontaneous rupture of membranes, disclosed that her pregnancy was unplanned and she had not previously sought antenatal care. Throughout the intrapartum period, her care was provided with sensitivity and compassion. While some investigation into her social situation was conducted using interpreting services during the postnatal period, her vulnerability was not fully recognised, and she was not referred to safeguarding services for a comprehensive assessment of her circumstances. Several safeguarding concerns, such as her social situation, lack of family support, concealed pregnancy, marital status, mode of entry to the UK, and giving birth outside her area of residence, were not adequately considered.

Recommendation

- Ensure that the number of women who require language support, and the support provided at each visit, is recorded systematically. This includes documenting the use of professional interpreting services at clinical care interactions and when supporting women through the navigation of care pathways, as well as recording when these services are not available. The resulting data should be used to implement quality improvement measures, and be assessed against existing NICE guidance.

Action: Integrated Care Boards (England), Health Boards (Wales and Scotland), Local Commissioning Groups (Northern Ireland), research funders.

4. Accessing the healthcare system

4.1. Key findings

- Language barriers significantly impacted recently arrived migrant women's access to maternity services, with challenges persisting from the initial booking through postnatal, bereavement, and follow-up care.

- Lack of coordination among healthcare providers led to missed opportunities for optimal care, particularly for women with existing risk factors, resulting in missed follow-up appointments and referrals.

4.2. Access to maternity services

Recent migrant women face multiple barriers to accessing medical and maternity care. Language barriers play a part, but this may be compounded by social factors (see section 3.7), including living in difficult or temporary accommodation, their partner living in another country, financial difficulties, lack of support services or simply not being provided with useable information regarding how to navigate a healthcare service that sometimes lacks flexibility. The assessors highlighted a lack of support on how to negotiate the UK maternity system across the care of women in the review. For some women, this may be as straightforward as being unaware of how to book for pregnancy care and, of concern, how to use ambulance services in an emergency (and, indeed, what might constitute an emergency). It was evident through the reviews that access to care is a challenge for recently arrived migrant women. A high proportion either presented unbooked (four women), or booked late in their pregnancy (13 women). Only five of the women who booked their pregnancy received antenatal care in line with national guidance. A lack of access to preconceptual and early pregnancy care prevents opportunities to provide support and treatment that may improve pregnancy outcomes and experience for women and families.

Currently there is little evidence regarding how to best support recently arrived migrant women to access maternity and wider healthcare services at the earliest opportunity. Understanding the barriers which prevent women from accessing healthcare is an important first step and should be a research priority. Consideration also needs to be given as to how the NHS might provide user-friendly information to women on how to access healthcare services, the importance of registering with primary care and how to contact maternity services. One possibility may be to develop a holistic assessment for migrant women of childbearing age that could be offered to them when they register with primary care. This assessment would aim to understand their psychosocial needs and any concerns they may have about engagement with services. Research into the feasibility of delivering such a service, as well as the impact of this and the acceptability to migrant women of any assessment would need to be fully explored as part of this work.

Similarly, there was evidence of barriers to accessing care in emergencies. Four women presented to emergency departments rather than maternity services or early pregnancy units as a way in to accessing care. If women choose to do this there must be established pathways to transfer on-going care immediately to maternity services. It may also be unclear to recently arrived migrants as to what situations they should use emergency services, or indeed how to utilise these services.

Vignette 6: An Afghan woman, who had interpreter support during her pregnancy, faced challenges during the postnatal period, including using public transport for her critically ill baby.

A woman from Afghanistan booked her pregnancy at 16 weeks gestation. The family arrived in the UK under the Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme and was living in temporary accommodation, which changed within the same city during the pregnancy. After initially booking at the hospital closest to them, they subsequently chose to give birth at the hospital that was known to them for providing care for refugees in the area. During her antenatal care there was consistent interpreter provision via LanguageLine and an in-person interpreter, although her first language was not recorded consistently. At 39 weeks of pregnancy she arrived by ambulance in labour, and her baby was born shortly afterward. After a nine day stay on the neonatal unit, during which time the mother remained an inpatient, her baby was discharged home. During the postnatal period, when her baby became extremely unwell, the family used public transport to take the baby to the hospital where the baby was born. The baby died following a cardiac arrest.

In view of how unwell this baby was, it would have been more appropriate to use the ambulance service. It is unclear why the emergency services were not utilised, and this perhaps highlights how difficult it may be to access emergency care appropriately when faced with an unfamiliar health care service. Many women may be unfamiliar with the NHS healthcare system and fear potential charges and costs associated with the access of emergency care services.

4.3. Coordination of care

Overall, there was a sense that the maternity system was not working effectively for the families in the review, resulting in reduced agency for women, which affected multiple areas of their care. This was evident in the lack of continuity of care providers and involvement of consultant-led teams, as well as in the failure to share information among all professionals and agencies involved in a woman’s care. A significant amount of information appeared to be held in isolated ‘silos’, further exacerbating issues of disconnected care.

For example, one woman who was well known to social services due to her homelessness, was not helped to register with a GP until the postnatal period. Whilst refugee and asylum-seeking women are entitled to book with a GP, disparities in support available to register and a lack of understanding regarding healthcare entitlement amongst healthcare professionals has previously been highlighted. The reviews highlighted an issue noted in the Royal College of Midwives’ (RCM) position statement on caring for migrant women: women who are recent migrants, particularly those seeking asylum, can be moved to unfamiliar areas at short notice, disrupting their care and severing their support networks within the community. Similar disruptions took place when women temporarily returned to their home countries during the antenatal period. This led to missed appointments and delays in scans and screening.

Opportunities to correct errors or recognise and address previous omissions were missed when additional agencies became involved. The absence of specifically established care pathways for these women further diminished their agency, leaving them marginalised and invisible within the system. This is despite the NICE recommendation to “Consider initiating a multi-agency needs assessment, including safeguarding issues, so that the woman has a coordinated care plan”. Developing standardised service pathways to assess and manage these specific issues may be beneficial.

Vignette 7: A Syrian refugee received proactive care, including appropriate interpreter services and referrals for housing and financial assistance.

A Syrian refugee was seeking asylum and booked her pregnancy at 14 weeks, her husband remained abroad and she was supported by family locally. Initially she was supported by the Asylum Health Bridging Team but this was withdrawn during pregnancy. The maternity team caring for her showed initiative in responding to this withdrawal of support, ensuring appropriate interpreters were sought and making a referral on to services to assist with housing and finance. Trisomy 18 was confirmed and there was clear evidence of extensive counselling and support from interpretation services to ensure she was informed about the diagnosis and prognosis. During her pregnancy, birth, postnatal and bereavement period there were 20 contacts noted. Only two of these occasions were without professional interpreting services.

4.4. Specific areas within the perinatal care pathway

Booking

Late booking was defined according to the NHS key performance indicator recommending that antenatal assessment should occur before 13 weeks, or by the twelfth week for women giving birth in Scotland. Late booking for maternity care was a recurrent theme in the reviews. Notably, all four women from Romania booked after more than 13 weeks. Late booking impacted upon the availability and opportunity to offer routine screening during the antenatal period, which may have adversely affected subsequent care. In a small number of the women this was due to the timing of their arrival in the UK, but this issue was compounded by difficulties in subsequently ascertaining what had occurred earlier in pregnancy, including screening and any maternal illness or fetal abnormality.

Vignette 8: A recently arrived nulliparous woman from India, whose late booking for pregnancy care was not properly considered, was not screened for gestational diabetes and, after a planned induction did not occur, her large baby was born via an emergency caesarean section at 37 weeks.

A nulliparous woman from India, recently arrived in the UK, booked her pregnancy with the community midwife at the end of her second trimester. She reported having received full antenatal care abroad, so her care plan did not initially account for her late booking and potential risk factors. During the antenatal period she was reviewed several times by the multidisciplinary team, but a professional interpreter was not used at any point. She was not screened for gestational diabetes throughout the antenatal period, and a scan performed around 34 weeks identified that her baby was large for gestational age. A plan was made for an induction of labour at term. At 37 weeks, she went to the maternity assessment unit with painful contractions, and an emergency caesarean section was performed. Her baby, who weighed more than 4kg, died shortly after birth. Almost all of her immediate postnatal care took place without the use of professional interpretation services, with the exception of one occasion when LanguageLine was used.

In general, it was unclear whether access to maternity care was not offered to these women, they were unaware of it or whether some chose not to access it. The latter may be related to a misconception that maternity care has to be paid for. For clinicians, information on migrant women’s entitlements to healthcare is available from professional organisations such as the RCM and British Medical Association (BMA), but communicating this information to women relies on them accessing healthcare in the first instance. Another potential reason for late booking is that typically all the information given to women is in English and language barriers may therefore affect the timing of women accessing services.

A combination of language barriers and a lack of proactive, robust, real-time risk assessment that captured the intricacies of maternity care for these groups of vulnerable women is likely to have contributed to the lack of personalised care planning seen.

Vignette 9: A Romanian woman, accompanied by her sister-in-law for interpretation, attended the Early Pregnancy Assessment Unit at 13 weeks pregnant but only resumed contact with maternity services at 25 weeks for her booking appointment.

A multiparous woman from Romania presented at the Early Pregnancy Assessment Unit at 13 weeks pregnant following an episode of bleeding. She was accompanied by her sister-in-law who provided interpreting services during the consultation. The sonographer advised that she must book her pregnancy with her GP and midwife as soon as possible and clearly documented the correct timing of all future screening scans. The woman did not initiate any further contact with maternity services until she was 25 weeks pregnant when she was seen by the community midwife for her booking appointment.

It is essential that commissioners and providers of maternity services have provision for multiple routes of access to care. These routes need to include the ability for a healthcare professional to make a direct referral in to the service on behalf of a woman with her consent, rather than the current expectation that a woman must self-refer to access care. Familiarity with the system, access to the internet and the ability to communicate the need to “book” a pregnancy cannot be presumed. Utilising existing tools to assess maternity disadvantage and health literacy needs for migrant women could support healthcare professionals in effectively planning onward care.

Emergency presentation, responding to ‘red flags’ and handover

Multiple examples of healthcare professionals needing to act on antenatal ‘red flags’ reported by women were evident

Vignette 10: An Afghan woman’s previous stillbirth was not thoroughly explored despite using an interpreter, leading to a lack of intensive monitoring and a subsequent stillbirth.

A woman from Afghanistan booked her pregnancy at 10 weeks gestation. Both she and her husband required interpreting services. Despite the presence of a face-to-face interpreter at the booking appointment, the maternal and obstetric history was described as "sketchy" by the booking midwife. A previous stillbirth, which occurred when the mother was still a teenager, was noted but not explored in further detail during the pregnancy. A more intensive care pathway, including serial growth scans, was not initiated as a result. Late in the third trimester, a stillbirth was confirmed after she self-referred to maternity triage with lower back and abdominal pain, along with an absence of fetal movements.

Late presentation with reduced fetal movements was a common theme, and it is unclear if this resulted from a lack of specific information provided to the women or a lack of understanding of the importance of this ‘red flag’. Six women reported reduced fetal movements of varying duration (days to weeks) at the time of assessment. There was evidence in only one woman’s notes that this information had been given to her in any other alternative format except verbally, and this was not in the woman’s preferred language. Five of these women presented with a stillbirth, having either waited for their next scheduled antenatal contact for advice or did not contact their maternity services until prompted by family members. Additionally, some ‘red flags’, such as female genital mutilation, a prior history of stillbirth and a large-for-gestational age baby on ultrasound scans (leading to delayed screening for diabetes) were not adequately addressed by professionals. As noted earlier, several women presented to emergency departments rather than maternity services or early pregnancy units, suggesting a lack of support in accessing specialist services such as maternity triage or the early pregnancy unit.

Improvement in the quality of interprofessional communication between teams was found to be needed in some reviews. Missed information and unstructured handovers concerning maternal risk factors, screening for maternal sepsis and chorioamnionitis led to delays in initiating essential treatment. An important aspect of handover is communicating maternal details if a baby requires neonatal intervention. Many fetal medicine departments provide documentation designed to be transferred into the baby’s notes after birth, whereas neonatal notes are generally structured around the baby and do not facilitate communicating information about the mother. This ‘silo’ approach is often compounded by the neonatal team missing the opportunity to obtain a complete maternal, obstetric, family, and social history when babies come under their care.

Neonatal care

Of the 25 pregnancies reviewed for this enquiry, 13 babies were liveborn but died in the neonatal period. There were clearly issues relating to language barriers and availability of interpreter services as discussed previously, but the review methodology prevented further ascertainment of whether the families’ migrant status impacted on neonatal care, in particular the ‘wrap around’ support delivered as part of the neonatal journey.

Bereavement and follow-up care

Notwithstanding the language barrier, access to bereavement care needed to be improved for these women and their families. Of the 22 stillbirths and neonatal deaths that occurred prior to initial hospital discharge, only 13 women overall had documented bereavement care in the community from their midwifery team or GP. This included five of the 13 women who had a neonatal death. It is perhaps time that bereavement care pathways in the UK are responsive and accessible for all families. Staff could benefit from more training in responding to pregnancy loss with cultural sensitivity and strengthening cultural safety training.

Documentation

Improvement to documentation has been noted to be needed in multiple previous confidential enquiries, and in this cohort of women it was no exception. Ethnicity and nationality were not well recorded and specific terms relating to citizenship, ethnicity and asylum status were used incorrectly. Recording of social risk factors could also be improved, as could previous medical and obstetric history that might be relevant to the current pregnancy. There were aspects of care that were declined by some of the women, but the clinical note proformas used were not structured to determine whether this was because of cultural beliefs or because of a lack of understanding of what was being offered.

Recommendations

- Ensure services provide advocacy for women who have been in the UK for less than a year, or do not speak or understand English, to support care navigation. This should incorporate midwifery and obstetric care when indicated.

Action: Home Office, Integrated Care Boards (England), Health Boards (Wales and Scotland), Local Commissioning Groups (Northern Ireland), research funders.

- Support research to understand women’s and healthcare professionals’ views on the barriers and facilitators to accessing and navigating maternity and neonatal care for women who have been in the UK for less than a year, or do not speak or understand English and require professional interpreting services. Use the findings to co-design services.

Action: NHS England, NHS Wales, Scottish Government and Northern Ireland Public Health Agency.

- Pilot the provision of an initial assessment appointment for migrant women of childbearing age when they first access health care services. The purpose would be to carry out a holistic assessment of their reproductive healthcare needs, provide information about reproductive health and availability of maternity services, and to understand any concerns they may have about accessing healthcare services.

Action: NHS England, NHS Wales, Scottish Government and Northern Ireland Public Health Agency, research funders.

- Develop provision for multiple routes of access to maternity care. These routes should include the ability for a health or social care professional, in any setting, to make a direct referral to maternity services on behalf of a woman with her consent.

Action: Integrated Care Boards (England), Health Boards (Wales and Scotland), Local Commissioning Groups (Northern Ireland).

5. Understanding why the babies died

5.1. Pathology

There were 25 babies born to the 25 women. Eleven of the babies were stillborn (one late fetal loss before 24 weeks’ gestational age, four between 24 and 36 weeks, and six at 37 weeks or later). Thirteen died in the neonatal period (two born at less than 24 weeks’ gestational age, six between 24 and 36 weeks and five born at 37 weeks or later). Four of these babies died within a few hours of birth, six within the first week of life and three were late neonatal deaths (between 8 and 28 days old). One baby survived beyond the neonatal period.

Post-mortem examination

Two of the 13 babies who died suddenly and unexpectedly in the neonatal period had a post-mortem examination performed under HM Coronial jurisdiction (15%). A post-mortem examination was offered to the parents of ten out of eleven babies (91%) who were stillborn. Five parents declined, three parents consented to a full post-mortem examination and two to an external only examination (a post-mortem rate of 46%). A post-mortem examination was offered to the parents of five of the eleven babies who died in the neonatal period (excluding the two Coronial cases), a rate of 46%. One set of parents consented to a full post-mortem.

The full post-mortem reports for seven of the eight babies were available to assessors. There was detail absent in the history section of the report in every instance; this was mainly in relation to obstetric history (current and previous) but it is not possible to determine if this was due to lack of information provided to the pathologist, or whether the pathologist chose not to include that information in the report.

The two post-mortems performed under HM Coronial jurisdiction were of babies who died in the neonatal period: one baby required neonatal care in hospital, but died at home at the end of the neonatal period; the other baby died within the first week of life after an uncomplicated birth, with no neonatal care required. The post-mortem examinations and reports were comprehensive.

Five of the consented post-mortem examinations were performed on stillborn babies and one on a baby who died during the neonatal period following a premature delivery and a postnatal diagnosis of bilateral renal agenesis. There was one post-mortem examination in which no clinicopathological correlation was included, only a list of findings. The Royal College of Pathologists post-mortem guidance stipulates a clinicopathological correlation should be included. There were a few factors absent in some of the reports, such as centile weight of the baby, but in general the quality of post-mortem reports was considered to be satisfactory, good or excellent.

Placental examination

Placental examination was performed for 20 babies’ deaths. The two babies who died later in the neonatal period and had HM Coronial post-mortems performed did not have placentas available for examination and in two further instances the placenta was not examined. It was not clear if the placenta from the baby who was live born (and remained alive) was submitted for examination. The proportion with a placental examination, after exclusion of those above, was 100% for stillborn babies and 82% for the babies who died in the neonatal period.

17 of the 20 placental reports were available for review. Six of those were associated with post-mortem examination, although as described above, in one only the provisional report was received. 16 full placental reports were therefore available to assess. The gestation of the baby was included in all the reports, but other aspects of the history, including maternal history, obstetric history and maternal BMI were not included in the report for at least half of the reports. However, it is not possible to determine whether that information was provided to the pathologist but not included in the report. The macroscopic description of the placenta followed the appropriate guideline in the majority of reports, although comment on the appearance of the membranes or maternal and fetal surfaces were absence in up to a quarter. A block key was absent in half the reports, which precluded assessment of appropriateness of sampling of the placenta. The microscopic description generally followed the guideline, with appropriate reference to the various compartments in the placenta. Around two-thirds of reports had a comment, although in those alongside post-mortem examination this was usually a combined comment. Overall, five of the 16 placental reports were considered to be of good or excellent quality, seven satisfactory and four unsatisfactory. The latter were affected by lack of macroscopic description, typographical mistakes, errors in sentence construction and in one instance the clinicopathological correlation was lacking, although as discussed above, it was unclear if this was due to inadequate information being provided to the pathologist.

Cause of death

There were two early neonatal deaths in which placental and post-mortem examination were not performed. The babies were known to have Trisomy 18 and given this, it is unlikely that further examination would have provided further information. Conversely, there was an intrauterine death of a baby with known Trisomy 18 for whom placental examination was performed; this showed placental changes including maternal vascular malperfusion which may be relevant to future pregnancies.

Four of the other neonatal deaths were related to an underlying congenital anomaly (renal agenesis, renal cystic disease, arthrogryposis and cardiovascular malformation). The diagnosis for all but the latter was known prior to death; the latter was identified on post-mortem examination.

Placental abruption was diagnosed clinically at delivery in one early neonatal death where no signs of life were identified despite resuscitation. Sepsis, acute chorioamnionitis or both were identified in three babies, all of which were also associated with extreme prematurity. Complications of prematurity were identified as the cause of death in a further baby. Hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy was present in one baby who died in the late neonatal period. No cause of death was identified in one of the babies despite a full post-mortem examination authorised by HM Coroner.

5.2. Follow-up appointment and letter

To help parents understand why their baby died, and to prepare for a future pregnancy they need a clear, supportive and compassionate follow-up appointment. There should be appropriate interpretation services provided and documented when required. Interpreting should not be carried out by family members. The correct professionals need to be present (obstetricians and/or neonatologists as appropriate) plus support staff (such as a bereavement midwife or nurse). All the results need to be available. If follow-on investigations are required, they should be organised with appropriate follow-up (either another meeting or a letter). After the meeting, a letter summarising the discussion, in the appropriate language, should be sent to the parents. The letter should cover the events leading to the perinatal loss, what was thought to be the cause including the results of any investigations, plans for future pregnancy and, if appropriate, advice regarding contraception. The letter should be written in a sensitive manner using plain language, explaining medical terms when necessary. It is considered best practice to address the letter to the parents directly. The GP can be written to separately, or copied into the parents’ letter

Of the 24 sets of parents whose baby died, only seven had a documented follow-up meeting. Of the 17 sets of parents who did not have a follow-up meeting, six either declined or cancelled the meeting. Seventeen sets of parents were sent a letter summarising the pregnancy and the care received by the mother and baby, but only one letter was translated into the parents’ own language. In this instance, the root cause analysis (RCA) report was also translated. Of the seven sets of parents who were not sent a personalised letter, the reasons why were documented in five. In two of these sets of parents, a trained interpreter was provided during the follow-up meeting.

Vignette 11: An Urdu-speaking mother experienced inconsistent interpreter use and lack of translated information throughout her pregnancy, and she did not receive professional interpretation services during a debrief appointment or follow-up letter.

An Urdu-speaking mother booked her pregnancy at 22 weeks after recently arriving in the UK. Her antenatal care showed inconsistent use of an interpreter, with no effort made to provide translated antenatal information. Serial growth scans during the third trimester identified a reduction in her baby’s growth. Later in the pregnancy, a Doppler scan was abnormal. Despite this, the plan for an induction of labour on her due date remained unchanged. Shortly before the planned admission, she presented with reduced fetal movements, and an ultrasound scan confirmed that her baby had died. The parents were offered a debrief appointment with a consultant obstetrician to discuss the investigation of the pregnancy, but professional interpretation services were not offered during this appointment. Although the follow-up letter was sensitive and mostly written in plain language, it was provided in English.

6. Overall findings

6.1. Overall summary of quality of care

A summary of the consensus findings of the assessors is provided in Table 2, indicating the quality of care provision for each mother-baby pair across all aspects of the care pathway.

| Overall quality of care | Mother-baby pairs N=25 |

% |

|---|---|---|

| Good care; no improvements identified | 1 | 4 |

| Improvements in care identified which would have made no difference to outcome [note 1] | 7 | 28 |

| Improvements in care identified which may have made a difference to outcome [note 1] | 17 | 68 |

Note 1: From the point of view of the baby, the assessors broadly interpreted ‘outcome’ to represent whether the care provision may have contributed to the death. From the mother’s perspective, ‘outcome’ was interpreted as her physical and psychological wellbeing and full consideration of her future fertility. These assessments were then combined to provide a holistic grade for each mother-baby pair.

6.2. Lessons to be learned

To improve maternity and neonatal outcomes for recently arrived migrant women who do not speak English, it is crucial to enhance the availability of professional interpreting services and targeted advocacy. Many recommendations from the previous confidential enquiry remain relevant, and further suggestions have been added to ensure these services are effectively measured and prioritised for research. A woman-centred approach to navigating NHS maternity care is essential, ensuring that these women can fully access and utilise the available services. Additionally, staff training should focus on better understanding their vulnerabilities and needs, enabling more effective support in navigating the healthcare system.

Recently arrived migrant women who are pregnant are presented with an unfamiliar system that is difficult to navigate. This is further compounded by the fact that where they are unable to speak or read English (either at all or at a level required for understanding), professional interpreting is not provided for the majority. A lack of specific pathways that lead and support them through maternity care further compounds this difficulty. A dearth of culturally safe care provision for women has been demonstrated to result in disconnected and uncoordinated care. Such concerns have been noted to impact upon women’s choice and access to specialised services and support. In some instances, this may have directly affected the outcome for both mother and baby. Whilst the digital maturation of NHS systems is underway, a lack of standardisation in record-keeping and agreed pathways across and within services risks women being lost in the system.

7. Recommendations and supporting evidence

| No. | New recommendations | Target audience | Supporting evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. |

Ensure that the number of women who require language support, and the support provided at each visit, is recorded systematically. This includes documenting the use of professional interpreting services at clinical care interactions and when supporting women through the navigation of care pathways, as well as recording when these services are not available. The resulting data should be used to implement quality improvement measures, and be assessed against existing NICE guidance. |

Integrated Care Boards (England), Health Boards (Wales and Scotland), Local Commissioning Groups (Northern Ireland), research funders. |

Section 3.5 In total for the 25 women there were 589 separate contacts with healthcare services. The number of contacts per woman ranged from eight to 53. No interpreting was documented as being provided at 296 (50%) of those contacts. Recommended interpreting services (either a trained in-person interpreter or LanguageLine) were documented as provided for 27% of contacts, with a trained in-person interpreter recorded as being provided for 38 (6%) contacts and LanguageLine provided for a further 126 (21%). While there were some women who were provided with interpreting services for the majority of their contacts, no one had professional provision at every contact. Additionally, the assessors noted that women who had mainly good interpreter provision had complex pregnancies and were under the care of the obstetric team. This highlights the need for the care of these women to be coordinated by a dedicated team. Interpreting was documented as being provided by a family member or friend for 56 contacts. In some situations, the assessors felt this was inappropriate. The most challenging stage of pregnancy care for providing interpretation services was during intrapartum care, where only 22 out of 72 (31%) contacts used either LanguageLine (16) or a trained interpreter (6). The lack of professional interpreter services was especially concerning during critical discussions or when sensitive information was involved, such as obtaining consent for procedures such as a caesarean section or explaining the importance of fetal movements during the antenatal period. When exploring the provision of interpreting services for routine and emergency care (attendance at the emergency department or triage), professional interpreting was documented as being provided for 35 of 94 (37%) of emergency contacts, using either trained interpreters or LanguageLine. Of 495 routine contacts, either trained interpreters or LanguageLine were used for 129 (26%). 36% of emergency contacts and 53% of routine contacts took place without any documented interpreting provision (50% combined). |

| 2. |

Ensure services provide advocacy for women who have been in the UK for less than a year, or do not speak or understand English, to support care navigation. This should incorporate midwifery and obstetric care when indicated. |

Home Office, Integrated Care Boards (England), Health Boards (Wales and Scotland), Local Commissioning Groups (Northern Ireland), research funders. |

Section 4.2 Recent migrant women face multiple barriers to accessing medical and maternity care. Language barriers play a part, but this may be compounded by social factors (see section 3.7), including living in difficult or temporary accommodation, their partner living in another country, financial difficulties, lack of support services or simply not being provided with useable information regarding how to navigate a rigid healthcare service. The assessors highlighted a lack of support on how to negotiate the UK maternity system across the care of women in the review. For some women, this may be as straightforward as being unaware of how to book for pregnancy care and, of concern, how to use ambulance services in an emergency (and, indeed, what might constitute an emergency). It was evident through the reviews that access to care is a challenge for recently arrived migrant women. A high proportion either presented unbooked (four women), or booked late in their pregnancy (13 women). Only five of the women who booked their pregnancy received antenatal care in line with national guidance. Four women presented to emergency departments rather than maternity services or early pregnancy units as a way in to accessing care. Section 4.4 Late booking for maternity care was a recurrent theme in the reviews. Notably, all four women from Romania booked after more than 13 weeks. Late booking impacted upon the availability and offer of routine screening during the antenatal period, which may have adversely affected subsequent care. In a small number of the women this was due to the timing of their arrival in the UK, but this issue was compounded by difficulties in subsequently ascertaining what had occurred earlier in pregnancy, including screening and any maternal illness or fetal abnormality. |

| 3. |

Support research to understand women’s and healthcare professionals’ views on the barriers and facilitators to accessing and navigating maternity and neonatal care for women who have been in the UK for less than a year, or do not speak or understand English and require professional interpreting services. Use the findings to co-design services. |

National Institute for Health and Care Research, research funders. |

Section 4.2 Recent migrant women face multiple barriers to accessing medical and maternity care. Language barriers play a part, but this may be compounded by social factors (see section 3.7), including living in difficult or temporary accommodation, their partner living in another country, financial difficulties, lack of support services or simply not being provided with useable information regarding how to navigate a rigid healthcare service. The assessors highlighted a lack of support on how to negotiate the UK maternity system across the care of women in the review. For some women, this may be as straightforward as being unaware of how to book for pregnancy care and, of concern, how to use ambulance services in an emergency (and, indeed, what might constitute an emergency). It was evident through the reviews that access to care is a challenge for recently arrived migrant women. A high proportion either presented unbooked (four women), or booked late in their pregnancy (13 women). Only five of the women who booked their pregnancy received antenatal care in line with national guidance. Four women presented to emergency departments rather than maternity services or early pregnancy units as a way in to accessing care. Section 4.4 Late booking for maternity care was a recurrent theme in the reviews. Notably, all four women from Romania booked after more than 13 weeks. Late booking impacted upon the availability and offer of routine screening during the antenatal period, which may have adversely affected subsequent care. In a small number of the women this was due to the timing of their arrival in the UK, but this issue was compounded by difficulties in subsequently ascertaining what had occurred earlier in pregnancy, including screening and any maternal illness or fetal abnormality. |

| 4. |

Pilot the provision of an initial assessment appointment for migrant women of childbearing age when they first access health care services. The purpose would be to carry out a holistic assessment of their reproductive healthcare needs, provide information about reproductive health and availability of maternity services, and to understand any concerns they may have about accessing healthcare services.

|

NHS England, NHS Wales, Scottish Government and Northern Ireland Public Health Agency, research funders. |

Section 4.2 Recent migrant women face multiple barriers to accessing medical and maternity care. Language barriers play a part, but this may be compounded by social factors (see section 3.7), including living in difficult or temporary accommodation, their partner living in another country, financial difficulties, lack of support services or simply not being provided with useable information regarding how to navigate a healthcare service which sometimes lacks flexibility. The assessors highlighted a lack of support on how to negotiate the UK maternity system across the care of women in the review. For some women, this may be as straightforward as being unaware of how to book for pregnancy care and, of concern, how to use ambulance services in an emergency (and, indeed, what might constitute an emergency). It was evident through the reviews that access to care is a challenge for recently arrived migrant women. A high proportion either presented unbooked (four women), or booked late in their pregnancy (13 women). Only five of the women who booked their pregnancy received antenatal care in line with national guidance. Four women presented to emergency departments rather than maternity services or early pregnancy units as a way in to accessing care. Section 4.4 Late booking for maternity care was a recurrent theme in the reviews. Notably, all four women from Romania booked after more than 13 weeks. Late booking impacted upon the availability and offer of routine screening during the antenatal period, which may have adversely affected subsequent care. In a small number of the women this was due to the timing of their arrival in the UK, but this issue was compounded by difficulties in subsequently ascertaining what had occurred earlier in pregnancy, including screening and any maternal illness or fetal abnormality. |

| 5. |

Develop provision for multiple routes of access to maternity care. These routes should include the ability for a health or social care professional, in any setting, to make a direct referral to maternity services on behalf of a woman with her consent. |

Integrated Care Boards (England), Health Boards (Wales and Scotland), Local Commissioning Groups (Northern Ireland). |

Section 4.2 Recent migrant women face multiple barriers to accessing medical and maternity care. Language barriers play a part, but this may be compounded by social factors (see section 3.7), including living in difficult or temporary accommodation, their partner living in another country, financial difficulties, lack of support services or simply not being provided with useable information regarding how to navigate a rigid healthcare service. The assessors highlighted a lack of support on how to negotiate the UK maternity system across the care of women in the review. For some women, this may be as straightforward as being unaware of how to book for pregnancy care and, of concern, how to use ambulance services in an emergency (and, indeed, what might constitute an emergency). It was evident through the reviews that access to care is a challenge for recently arrived migrant women. A high proportion either presented unbooked (four women), or booked late in their pregnancy (13 women). Only five of the women who booked their pregnancy received antenatal care in line with national guidance. Four women presented to emergency departments rather than maternity services or early pregnancy units as a way in to accessing care. Section 4.4 Late booking for maternity care was a recurrent theme in the reviews. Notably, all four women from Romania booked after more than 13 weeks. Late booking impacted upon the availability and offer of routine screening during the antenatal period, which may have adversely affected subsequent care. In a small number of the women this was due to the timing of their arrival in the UK, but this issue was compounded by difficulties in subsequently ascertaining what had occurred earlier in pregnancy, including screening and any maternal illness or fetal abnormality. |

| Previous recommendations with continued relevance |

|---|

|

P1. Ensure the digital maternity record includes details of language needs including the use of formal interpreter services, to ensure that these are taken into consideration at all interactions, including in emergency situations. (MBRRACE-UK 2024) |

|

P2. Develop national guidance and training for all health professionals to ensure accurate recording of women’s and their partner’s self-reported ethnicity, nationality and citizenship status, to support personalised care. (MBRRACE-UK 2023) |

|

P3. Provide maternity staff with guidance and training to ensure accurate identification and recording of language needs in order to support personalised care. This should include guidance about when it is appropriate to use healthcare professionals as interpreters. (MBRRACE-UK 2023) |

|

P4. Provide national support to help identify and overcome the barriers to local, equitable provision of interpretation services at all stages of perinatal care. This should include the resources to provide written information and individual parent follow-up letters in languages other than English. (MBRRACE-UK 2023) |

|

P5. Develop a UK-wide specification for identifying and recording the number and nature of social risk factors, updated throughout the perinatal care pathway, in order to offer appropriate enhanced support and referral. (MBRRACE-UK 2023) |

|

P6. Ensure maternity services deliver personalised care, which should include

identifying and addressing the barriers to accessing specific aspects of care for each individual. |

|

P7. Further develop and improve user guides for perinatal services, to empower women

and families to make informed decisions about their care and that of their babies. |

|

P8. Ensure that guidance on care for pregnant women with complex social factors is updated to include a role for networked maternal medical care and postnatal follow-up to ensure that it is tailored to women’s individual needs and that resources in particular target vulnerable women with medical and mental health co-morbidities and social complexity. (MBRRACE-UK 2023) |

|

P9. Healthcare professionals should be given training on the specific social, religious and psychological needs of women who are recent migrants, asylum seekers or refugees (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2010) |

8. Enquiry materials

9. Acknowledgements

9.1. Assessors

Intitial reviews of care were conducted by members of the MBRRACE-UK maternal mortality and morbidity assessors group. Details of the assessors can be found in the Saving Lives, Improving Mothers' Care 2024 - Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2020-22 report.

The following additional assessors reviewed any neonatal care provided:

- Morag Campbell, Consultant Neonatologist, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde

- Mallinath Chakraborty, Consultant in Neonatal Medicine, Cardiff and Vale University Health Board

- Alan Fenton, Consultant Neonatal Paediatrician, The Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

- Edile Murdoch, Consultant Neonatologist, NHS Lothian

9.2. Report contributors

- Natasha Archer, Consultant Obstetrician, University Hospitals Leicester NHS Trust

- Margarita Bariou, Midwife, Birmingham Women's and Children's NHS Foundation Trust

- Kailash Bhatia, Consultant Anaesthetist, Manchester University NHS Trust

- Morag Campbell, Consultant Neonatologist, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde

- Mallinath Chakraborty, Consultant in Neonatal Medicine, Cardiff and Vale University Health Board

- Philippa Cox, Consultant Midwife, Homerton University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

- Tina Evans, Clinical Advisor, MBRRACE-UK

- Allison Felker, Senior Researcher, MBRRACE-UK

- Alan Fenton, Consultant Neonatal Paediatrician, The Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, MBRRACE-UK collaborator

- Ian Gallimore, Project Manager, MBRRACE-UK

- Nicola Harrison, Patient Safety Midwife, The Queen Elizabeth Hospital King's Lynn NHS Foundation Trust

- Stephanie Heys, Consultant Midwife, North West Ambulance Service NHS Trust

- Samantha Holden, Perinatal and Paediatric Pathologist, University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust

- Sara Kenyon, Professor of Evidence-Based Maternity Care, University of Birmingham, MBRRACE-UK collaborator

- Becky MacGregor, General Practitioner

- Colin Malcolm, Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist, NHS Lanarkshire

- Penny McParland, Consultant Obstetrician, University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust

- Edile Murdoch, Consultant Neonatologist, NHS Lothian

- Benash Nazmeen, Assistant Professor in Midwifery, University of Bradford

- Georgie Page, Research Assistant, MBRRACE-UK

- Louise Robertson, Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist, Liverpool Women's Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

9.3. Additional acknowledgements

10. Further information

10.1. Funding

The Maternal, Newborn and Infant Clinical Outcome Review Programme, delivered by MBRRACE-UK, is commissioned by the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) as part of the National Clinical Audit and Patient Outcomes Programme (NCAPOP). HQIP is led by a consortium of the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, the Royal College of Nursing, and National Voices. Its aim is to promote quality improvement in patient outcomes. The Clinical Outcome Review Programmes, which encompass confidential enquiries, are designed to help assess the quality of healthcare, and stimulate improvement in safety and effectiveness by systematically enabling clinicians, managers, and policy makers to learn from adverse events and other relevant data. HQIP holds the contract to commission, manage, and develop the National Clinical Audit and Patient Outcomes Programme (NCAPOP), comprising around 40 projects covering care provided to people with a wide range of medical, surgical and mental health conditions. The programme is funded by NHS England, the Welsh Government and, with some individual projects, other devolved administrations and Crown Dependencies.

More details can be found on the HQIP website.

10.2. Stakeholder involvement

Organisations representing parents and families are involved in the MBRRACE-UK programme as part of the ‘Third Sector’ stakeholder group, identifying possible areas for future research and helping to communicate key findings and messages from the programme to parents, families, the public and policy makers, including through the development of lay summary reports. A full list of organisations can be found in the acknowledgements.

10.3. Cohort

Deaths reviewed are from England, Wales, and Scotland, for the period 1 January 2022 to 31 December 2022 inclusive.

10.4. Attribution

This report should be cited as:

Kenyon SL, Gallimore ID, Evans TC, Page GL, Felker A, Fenton AC (Eds), on behalf of the MBRRACE-UK Collaboration. MBRRACE-UK Perinatal Confidential Enquiry, The care of recent migrant women with language barriers who have experienced a stillbirth or neonatal death: State of the nation report. Leicester: TIMMS, Department of Population Health Sciences, University of Leicester. 2024.

Published by:

TIMMS

Department of Population Health Sciences

University of Leicester

George Davies Centre

University Road

Leicester LE1 7RH

11. Version history

| Version | Details of changes | Release date |

|---|---|---|

| 1.0. | First published. | 12 December 2024 |